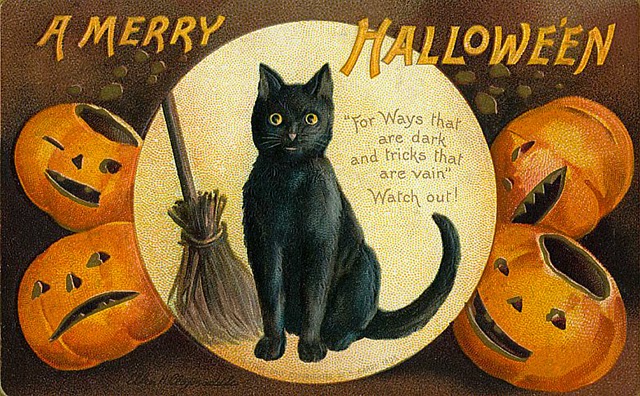

We’ve all seen it: the snarling, hissing black cat figure of Halloween that has been a staple of the holiday for more than a century. For many, this comically scary representation of our beloved house cats is as much a part of Halloween as ghosts, candy corn and pumpkins. But few know the fascinating intricacies of the cat’s relationship with the holiday, a history that goes a long way to understanding the way we regard felines even today.

The shared history of humans and the domesticate cat is complex, marked by both devotion and animosity (often times simultaneously) and does not follow a single path. What’s particularly notable is that while cats may have been persecuted in one part of the world as minions of evil, they could be cherished and revered in another as mousers and companions. But regardless, it is undoubtable that the cat has suffered greatly due to its association with human evil, and it is a testament to the cat’s loveability, reproductive prowess and adaptability that they are still with us today.

By no means an exhaustive account, what follows is a rough trajectory of the cat’s association with evil in the Western European Christian tradition, that which eventually led to the Halloween we know today. For more reading, please see the list of references at the end of this post.

So Happy Halloween, Cat Connection friends! In the midst of all the festivities of the day, be sure to hug your kitties and keep them indoors, for this evening the night is dark and full of terrors that stretch deep into our shared history with the cats we love.

The Cat Goddesses of the Ancient World

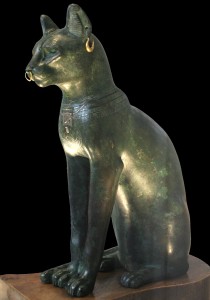

The relationship of cats and humans begins in Egypt and the surrounding region, where wildcats living on the peripheral of human civilization were slowly integrated into a closer relationship with people. Evidence of early cats kept as companions in Egypt stretch as far back as 6,500 years ago, and it is likely that during this time the modern domestic cat began to take shape. Larger than the domestic cat of today, these cats were cherished for their vermin control, particularly following the spread of the black rat from India and Southeast Asia via trade routes 2,600 years ago.

About 3,500 years ago, cats began to feature more frequently in Egyptian cults and religion, particularly with the goddess Bastet. She was originally depicted as a woman with a lion’s head attended by smaller felines, but the growing ubiquitousness of domestic cats eventually transformed not only representations of the goddess, but also her association in people’s minds. As John Bradshaw notes in Cat Sense:

“Originally a simple goddess who protected humankind against misfortune, she later became associated with playfulness, fertility, motherhood, and female sexuality – all characteristics of domestic cats.” (35)

As domestic cats spread to Greece and Rome, most likely as exotic imports at first, the cat became associated with the goddess of the hunt, Artemis in Greece and Diana in Rome. Cults in veneration of the goddess, including Bastet, persisted for centuries, even through the sixth century in some parts of Europe.

Formalized Hostility Towards the Cat

The domestic cat spread rapidly throughout Europe in the centuries following its emergence in Egypt. Though just as often regarded as disposable, the cat was also cherished for its mousing abilities and independent nature. For years, cats were depicted positively in religious texts, and the Christian Church held a generally benevolent attitude towards the feline throughout most of the Dark Ages, as cats featured heavily in monastic life.

Unfortunately, this benevolence began to shift in 391 CE, when emperor Theodosius I banned all pagan worship, including the worship of Bastet and Diana. Cats, still heavily associated with these goddesses, were at first left largely untouched by this proclamation and still enjoyed a relatively positive reception in rural communities, those furtherest away from the reach of the Church.

However, all of this changed in the 13th century. On June 13, 1233, Pope Gregory IX published Vox in Rama, which identified cats, specifically black cats, with Satan, thus beginning the wholesale persecution of felines in continental Europe and resulting in the deaths of millions of cats over the next 300 years.

The political reasons for this sudden demonization of cats are relatively simple. In an attempt to eliminate the supposed worship of the Devil, i.e., veneration of anything besides the Holy Trinity, the Church effectively sought to eliminate anything remotely associated with pagan rites. Cats, still associated with Bastet and Diana, were drawn into the fire as a result. It is also likely that such a declaration was a subtle admonishment of Islam, the most significant rival religion of the time and one that had historically featured kindness to cats.

However, even the very nature of the feline may have set it up for wholesale persecution. As Katharine M. Rogers notes in Cat:

“In medieval and early modern periods, when a hierarchical order in society and nature was assumed to be right and necessary, [cats’] disregard for human wishes and expectations was unpleasantly disconcerting. Moreover, because the natural dominion of man was ordained by providence, their refusal to recognize it demonstrated antagonism to God as well as man. Therefore, it seemed likely that their secret nocturnal world was presided over by the Prince of Darkness.” (51)

Thus, the cat’s perceived independence and indifference to the wants of human companions, once cherished, was suddenly associated with antagonism to the natural order as determined by God.

Witches and their kitty familiars

Following the Church’s formal condemnation of cats, it was not long before felines were regularly associated with witches, usually marginalized female figures that had run afoul of the Church or their presiding local government. Officially, the Witchcraft Act was passed in 1542 in England, and by 1580, 13% of all criminal hearings involved some charge of witchcraft.

Though not the sole animal identified as a familiar, a sort of non-human companion used to inflict evil by witches or the shape a witch could take at will, in ways, cats were ideally suited for the role. Not only did a cat’s nature – solitary hunters largely indifferent to the comings and goings of humans – speak to a congress with the Devil, but the behavior of a cat’s human companion could also suggest supernatural leanings. As Rogers notes, “close physical contact, a shared language, and the ever present cat as companion,” to an onlooker, could appear otherworldly (52). Add to that the symptoms of a cat allergy – wheezing, sneezing, watering eyes – and it is no wonder cats were held as the consorts of witches for so long.

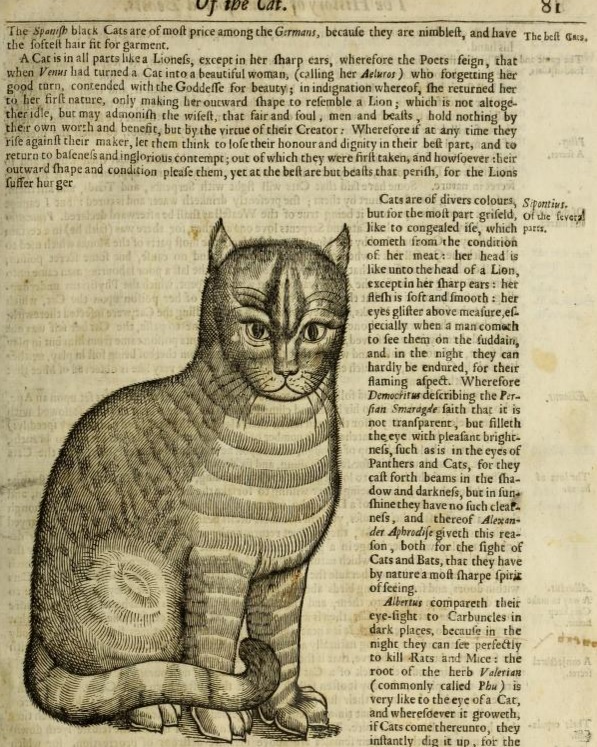

Edward Topsell’s The Historie of Fourefootid Beastes, 1607

That the link between witches and cats was seen as undeniable fact is evidenced by Edward Topsell’s The Historie of Fourefootid Beastes, the first major published work on animals, which combined myth, legend and folk lore to provide accounts of the world’s animals, both real and imaginary.

On the cat, Topsell writes of “what harmes and perils come unto men by this beast,” including breath that destroys the lungs, poisoned flesh, and venomous teeth. Most damning, he writes:

“It must be an unclean and impure beast that liveth only upon vermin and by ravening… likewise the familiars of witches do most ordinarily appear in the shape of cats, which is an argument that this beast is dangerous to soul and body.”

Witch Trials – Trial of Ursula Kemp, St. Osyth (England, 1582)

Unsurprisingly, cats were often discussed at length in trails of accused witches, the inclusion of which often follows a clear, formulaic pattern. As Katherine Howe notes in The Penguin Book of Witches, the trial of Ursula Kemp “establishes a pattern for witch trials to come. Her marginal status within her community, her alleged crimes, the use of children as witnesses, her familiar spirit… all reappear in North American witch trials a century later” (7).

At the trial of Ursula Kemp in 1582, her own eight-year-old son, Thomas Rabbet, provided the detailed account of his mother’s familiars, two of which take the form of a cat:

The said Thomas Rabbet saith that his said mother Ursula Kemp, alias Grey, hath four several spirits, the one called Tyffin, the other Tittey, the third Pigeon, and the fourth Jack and being asked of what colors they were, saith that Tittey is like a little gray cat, Tyffin is like a white lamb, Pigeon is like a toad, and Jack is black like a cat.” (10)

Kemp was accused of consorting with these familiars, in particular of breaking bread with them and drinking beer together. It did not end well for her.

Witch Trials – Salem (Salem, Massachusetts, 1692)

This pattern is repeated in perhaps the most well-known witch trial, that which took place in Salem, MA in 1691 – 1692. Here, the accused Tituba, a slave living in the home of one of the afflicted girls, speaks repeatedly of encountering “Two cats: a red cat and a black cat” and of seeing another accused woman, Sarah Good, with a cat numerous times.

Tituba recounts that the cats, familiars of witches and agents of the devil, demanded that she serve them:

“After prayer, [the cats] scratched me because I would not serve them and when they went away, I could not see. But they stood before the fire.”

Romanticized Fantasy Cats, Still Evil

As the fear of witches waned in the 18th century, the relationship between humans and cats began to improve. Poets, writers and authors began to embrace the cat as emblems of non-conformity, mystery, and eroticism. The very characteristics that associated cats with evil in the centuries before were now depicted positively, and by the 19th century, cats were kept as cherished pets, though still regarded with hostility by many.

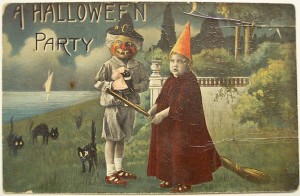

It is during this time that witchcraft and cats became an artistic and cultural trope, no longer a legitimate cause of concern. Thus, in the 20th century, when the Halloween as we know it today began to take shape from its ancient roots, the centuries-long history of the cat’s association with evil was transformed into the playful, often picturesque fantasy we still encounter today.

A Word of Caution

While it may be easy to see the cat’s historical affiliation with evil and witchcraft as nothing to be concerned with anymore, cats, particularly black cats, are still the victims of enormous cruelty and superstition that owes much to fear started centuries ago. There is something to be said, as cat behaviorist Pam Johnson-Bennett recently wrote, about the perpetuation of negative cat stereotypes through Halloween decorations.

While this particular history of cats is fascinating in its bizarreness, it is truly the responsibility of all Cat People to change the way cats are seen, especially at Halloween.

More Reading

Cat. Katharine M. Rogers.

Cat Sense. John Bradshaw.

The Penguin Book of Witches. Ed. Katherine Howe.